What happened to the lost colony of Roanoke Island is one of history’s biggest unanswered mysteries. The first English settlement in the New World, founded in August 1585 by Queen Elizabeth I’s favourite, Sir Walter Ralegh, was discovered abandoned in 1590 with no sign of the inhabitants. Dr. Eric Klingelhofer researches…

About Lost Colony of Roanoke

On the morning of August 18, 1590, a party of seamen from the Moonlight and the Hopewell, two English privateering ships, clambered up from a sandy beach to penetrate open woods. They followed the lead of an old man whose cries would have gotten increasingly desperate: “Eleanor! Ananias! Anybody! Is there anyone here? “The sailors arrived on Roanoke Island in modern North Carolina, headed by John White, governor of Queen Elizabeth I’s North American colony, Virginia.”

White was looking for his daughter Eleanor and her husband, Ananias Dare, as well as any other English settlers on the island. Eleanor and Ananias were members of the colony he had left three years before, together with his baby granddaughter Virginia.

White had gone to England in 1587 to obtain desperately needed supplies from Sir Walter Ralegh for the colonists who had spent the winter on Roanoke. His return to America was quickly marred by complications. His ship was taken by French pirates on his first try, and he was severely injured in the struggle. His attempts were further thwarted by a royal proclamation prohibiting any shipment due to the Armada threat.

Even when White was able to return in 1590, another calamity occurred the day before his quest for Roanoke. A captain and many crewmen perished in heavy waves while attempting to reach Roanoke Island via the Outer Banks’ treacherous sand bars. Despite this, the seamen continued on, rowing around Roanoke and anchoring off its northern end, where the inhabitants had dwelt. However, no one responded to White’s calls. There was no one there. White discovered that a new powerful fort had been built but had since been abandoned, holding only discarded, heavy materials. The settlement’s dwellings have all been destroyed and removed. The 117 members of the Lost Colony were never found.

New Eden

White had gone to England in 1587 to obtain desperately needed supplies from Sir Walter Ralegh for the colonists who had spent the winter on Roanoke. His return to America was quickly marred by complications. His ship was taken by French pirates on his first try, and he was severely injured in the struggle. His attempts were further thwarted by a royal proclamation prohibiting any shipment due to the Armada threat.

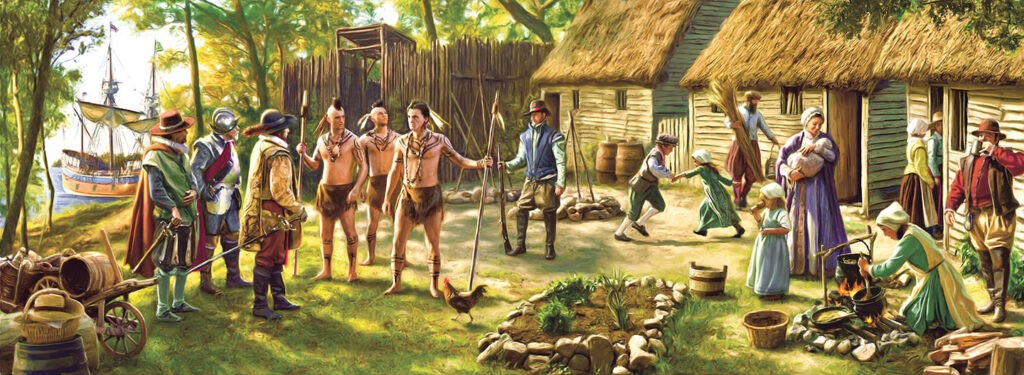

Ralegh’s attention was drawn to the North Carolina coast, which juts out into the Gulf Stream path used by Spanish galleons to transport gold and silver from Mexico and Peru. In 1584, a single English vessel arrived on the Carolina coast and was quickly escorted to Roanoke Island by native peoples. Roanoke was described as a new Eden based on its brief visit, with agriculture, game, and friendly Indians.

Ralegh soon dispatched a military expedition to explore the new territory he dubbed Virginia in honour of the queen. The men, led by Ralph Lane, a relative of Elizabeth’s stepmother, Queen Katherine Parr, were to assess the area’s potential for valuable commodities and to use it as a base to target Spanish commerce.

Lane discovered that the area had some potential, but it was hardly a new Eden, and its shallow coastal waters were unsuited for battleships. Ralegh had taken great care to offer professional documentation on the undertaking, which he used to solicit money – and, ideally, royal backing – for subsequent settlement. He dispatched John White, a well-known royal artist, to join the flotilla that conducted the initial expedition.

White created for him watercolour sketches of North American flora, animals, and aboriginal peoples that are now among our greatest images from the Age of Exploration.

Ralegh also sent the mathematician-scientist Thomas Harriot to spend a year on Roanoke with Lane, creating nautical charts, studying the Algonquian language from Manteo, a noble from the friendly coastal Croatoan tribe, and collecting samples to examine for mineral and pharmacological value.

Lane’s troop, however, was frantic for promised supplies by the spring of 1586, confronted with diminishing supplies and increasingly hostile local tribes. Sir Francis Drake’s fleet gathered outside the banks of Roanoke after attacking Spanish ports in the Caribbean. However, before he could save the colony, the fleet was devastated by a cyclone. Lane accepted his invitation to return to England with reluctance.

The Second Colony

This was the situation in the winter of 1586–7, when Ralegh’s artist, John White, proposed to lead a civilian colonial expedition to Virginia. White had only been in Virginia for a few weeks in 1585, so he had not experienced the poverty and peril that Lane’s troops would eventually encounter.

The majority of them that sailed with him appeared to be from London, with artisan and middle-class origins. Whole families joined the second colony, while others sailed with the expectation that their families would follow. Economic opportunity was most likely the primary motive for their exodus, while religious freedom may possibly have played a role.

In the summer of 1587, ships from the second colony landed on the shore near Roanoke. There was a disagreement between the captain, who commanded at sea, and the governor, who commanded on land. Ralegh eventually told White to transport the immigrants north to the deep-water Chesapeake Bay, which Lane felt would be a better base for privateers and closer to the mountain supplies of copper, gold, and silver. The captain, on the other hand, does not appear to have been obliged by these orders, since he refused to transport the passengers any farther.

When the company arrived, the Roanoke town was deserted, the fort was in ruins, and the mainland Indians were hostile. To make matters worse, a landing mishap resulted in the rotting of much of the food supply. After repairing old houses and constructing new ones, the colony’s founders determined that a direct appeal to Ralegh was required, and that only Governor White could make it. Before leaving, White observed two significant events: the birth of his granddaughter Virginia, the first English child born in the New World, and Manteo’s baptism and induction as Lord of Roanoke.

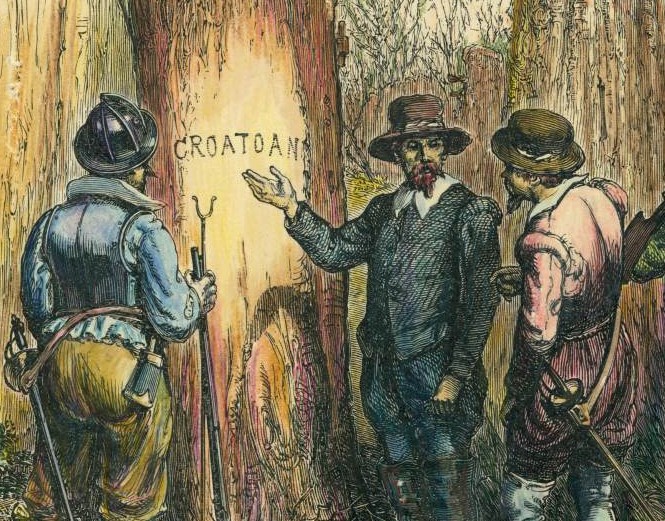

The return of John White in 1590 proved that this distant England had been a dream. There was no colony, no settlement, and no Christian Indian dominion. Fresh tracks were discovered on the Roanoke beach by White and the sailors, indicating that the local Indians were hostile or terrified of the English search expedition.

The searchers planned to sail south to the friendly Croatoan tribe’s centre around Cape Hatteras, interpreting the initials ‘CRO’ carved into a tree as the name of Manteo’s friendly Croatoan tribe (White subsequently remembered it also as a complete spelling on a gate post). However, once onboard ship, harsh weather pushed them further and further north, till they had no choice but to return home.

Why Roanoke Colony Disappear?

So, what happened to the Lost Colony? Why did it vanish? When discussing the causes of social and demographic disasters, there are typically four broad possibilities: war, hunger, disease, and death. All four most likely brought Elizabethan Virginia to an end. We know that the Spanish never discovered the colony, but fear of being discovered may have driven it to relocate further west. White suspected that a shift “50 miles further up into Maine” was planned. In 1587, the adjacent mainland Indians were definitely hostile.

The body of an Englishman who had gone crabbing was discovered soon after the civilians arrived, full with arrows and disfigured. Another motivation to leave Roanoke was the local danger.

We also know that Lane’s men experienced a severe food scarcity in 1586, and that White returned to England in 1587 because the supplies had been spoiled. The civilian colony lacked the clout to persuade local groups to share their winter stockpiles. Famine would later create the “starving time” at Jamestown, when Indians refused to trade food. Because North Carolina lacked a strong, powerful native government to maintain the colony, it is likely that it broke up into smaller groupings, each keen on survival. Disease – possibly the Plague itself – would repeatedly drain the vigour of the nascent colony at Jamestown. In Roanoke, infectious illnesses may have had a similar influence.

If uncontrolled, these three causes resulted in the fourth – death. White’s crew found no graves or human bones during their hours on Roanoke, suggesting that the colonists may have departed the island before suffering such a fate. It appears that the surviving will then break into two or more groups. On the Outer Banks, one would have waited for supply ships among the Croatoan tribe. The other would have sailed 50 miles west to a more secure and prosperous area. The Jamestown colonists had heard second-hand reports about a few Roanoke survivors living among the natives in this region, but these accounts were never proven.

The British Museum was then invited in 2012 by the First Colony Foundation (FCF), a group of historians and archaeologists exploring Ralegh’s American colonies, to investigate paper patches on its manuscript map La Virginea Pars, produced by John White for Sir Walter Ralegh. The museum personnel quickly uncovered a Renaissance fort sign beneath one patch, and a faint representation of a fortified town on the patch’s surface, maybe painted in invisible ink. The patch was located around 50 miles from Roanoke Island, near the western extremity of the Albemarle Sound.

FCF’s remote sensing and fieldwork uncovered no such fort in a five-mile radius, although its crews did unearth metal artefacts and Tudor-period household ceramics at one location near a modern Algonquian settlement. Because the pottery would not have been transported by Lane’s men in 1585–6, FCF researchers declared in 2015 that Site X (for unknown) was the probable site of a few Lost Colony members for a brief time. Excavations will restart in late 2016 to better understand the nature of Site X and to uncover new clues to the four-century-old mystery of the Lost Colony.